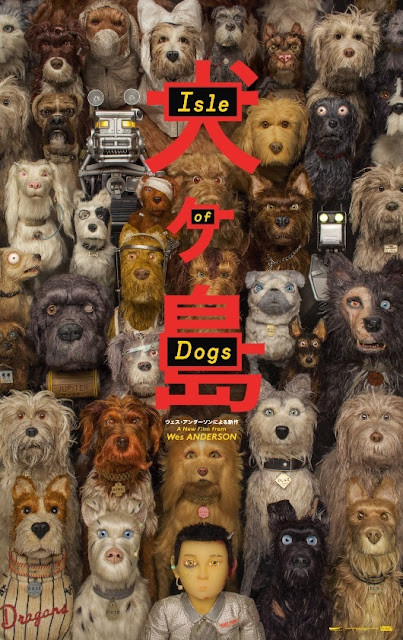

Isle of Dogs

Isle of Dogs is a stop-motion cartoon from Wes Anderson about how dogs are man's best friend.

The film nearly reviews itself from the mere description - the eccentric hipster's witty writing, outsider characters, detailed dollhouse-like worlds, and undercurrents of gentle warmth and shocking violence either charm your pants off or immediately repulse you. The addition of stop-motion animation and subject of dogs, similarly, are things that you probably know either work for you or don't. Isle of Dogs is one of Anderson's wittiest, most detailed, warmest, and most charming films yet, and you want to just hug the movie and scratch it behind the ears - unless you're not on the Wes Anderson-stop motion-dog wavelength, in which case you may as well be a cat person with a dog allergy stuck in a dog kennel.

While this isn't Anderson's first foray into stop-motion - following Fantastic Mr. Fox nearly a decade ago - I believe it is his first science fiction film, technically speaking. 20 years in the future, a disease spreads through dogs, and Mayor Kobayashi ultimately bans dogs entirely, transporting them to a nearby garbage island. The dogs being dogs, they form packs, of which we follow one particular group: Rex (Edward Norton), King (Bob Balaban), Duke (Jeff Goldblum), Boss (Bill Murray), and tough, grouchy street dog Chief (Bryan Cranston). Their life of scavenging is thrown out of whack when Atari Kobayashi (Koyu Rankin), the young nephew of the Mayor, crash-lands a junior plane on the island, searching for his own beloved canine, Spots (Liev Schriber). The pack aids him in his quest, even as Mayor Kobayashi sends his goons and robot dogs to "rescue" Atari.

The heart of the story is the relationship between a boy and a dog, dramatized between Atari and Chief. Chief, perfectly embodied by the gruff-voiced Cranston, has always lived on the streets, and has a thick skin to get through. Atari, hopeful that he'll find Spots, but fearful that Spots has died on the vicious island, bonds to Chief much more quickly than Chief bonds to him, but much of that is simply the layers of emotional shielding Chief has built up over the years, and his denial of those emotions. This kind of relationship, between the tough loner not in touch with his heart and the more openly emotional kid is an oldie but a goodie; and when it's done with both humor and sincerity, and follows a dynamic and convincing arc, it's absolutely magical, as it is here.

Anderson often has an undercurrent of sadness and shocking (yet cartoonish) violence in his comedies; by centering the film on dogs being exiled and dangling the possibility of their death over them (and being willing to pull the trigger on that), Anderson makes that sad undercurrent as strong as in Royal Tenenbaums and The Grand Budapest Hotel. Similarly, by really capturing canine personalities and melding them with his quirky humor, he makes one of his funniest and warmest films.

Further, by having such a scale to set it on, he's able to quietly make a beautiful statement about the world that compliments his last film. Grand Budapest Hotel looked at the past with nostalgia, but also saw the vile ugliness that rippled through it. It's not something to return to, even as you love it. Isle of Dogs looks to the present, and sees those who want to control it by demonizing a part of society, riling up the people against those invented enemies, and pushing them out of the country or isolating them in areas that may as well be trash islands. But it also sees a future where children can band together and save this world, and build a more beautiful one, a world of love and joy and adventure.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the stop-motion animation is astounding. The dogs, in particular, move with that unmistakably canine mix of graceful strength and clumsiness; animated as smoothly as Kubo and the Two Strings, but with the dancing fur of the original King Kong giving it extra life and a charming artificiality. I especially love how their mouths move; their jaws look entirely canine, while their lips sync just enough with the dialogue to fit, while still seeming like the way dogs move their lips. As with Anderson's previous stop-motion cartoon, Fantastic Mr. Fox, the frame-by-frame meticulousness not only perfectly suits Anderson's style, but seems to free him up. His style has gotten so ingrained and recognizable it shouldn't feel fresh, but here, it actually does.

The story, ranging across the isle and the nearby city, allows Anderson a vast canvas on which to create another of his perfect, densely detailed toy worlds. The movie is a joy to look at in every frame.

However, that setting, beautiful though it is, does leave one lingering question: is this cultural appropriation?

|

| I mean, what isn't these days? |

And yet, for all Anderson's more than evident love of the culture of Japan, it's questionable at best whether he does well by the people of Japan. This is where the language barrier becomes a problem. All these dogs are played by white dudes (and, briefly, Scarlett Johansson), and speaking English, and thus we form a much easier bond with them than with the Japanese characters. If this was consistent, it might be easier to roll with, but it's made all the more obvious because one of the two main humans is Tracy Walker, a foreign exchange student obsessed with the Kobyashi conspiracy and Atari's story, and who actively fights the conspiracy and raises the kids of the city into revolt. She's a great character, adorably voiced by Greta Gerwig, but because she speaks English, and because she's the active white hero who makes herself a leader, it means that the easiest human to identify with is the white chick fixing what the Asians screwed up. The result does understandably, for some viewers, feel dehumanizing.

This is not to say that Anderson intentionally or even completely dehumanizes the Japanese characters. After all, even though we can't understand what he's saying, we absolutely bond with the adventurous Atari, and he drives the story as much if not more than Tracy. Many of the supporting Japanese humans, while briefly sketched, are engaging in their own right. Even Mayor Kobayashi ultimately reveals himself as a more complex figure than he appears. So it's not clean-cut. (When is it ever?) The Hollywood Reporter has a solid article about it, which itself references other articles from actual Asian-American writers upset by the film.

On the flipside, here's an interview with Nomura discussing the story and his involvement, joined by Gerwig, who, in typical Gerwig adorableness, seems to be doing the interview in her pajamas.

So I'm conflicted in how to feel about all this. On the one hand, I see why Tracy is problematic, but I feel like Atari is so engaging he makes it somewhat moot. And as an artist, I very much believe that artists should be able to tell the stories they're driven to tell. There has, however, been a history in Hollywood of dehumanizing people of other cultures, and while that problem really is part of every culture in every history, the worldwide ubiquity of Hollywood givesithem a level of responsibility here that perhaps we should be hypersensitive to. Sure, we don't want to dilute films to blandness and strangle artistic creativity, but the difficulty of non-white males to tell the stories of their people - or any stories - has warped our visions and output. Isle of Dogs does a far better job than most Hollywood films in its treatment of Japanese culture, but that doesn't mean there isn't room for criticism or improvement, or that we shouldn't be striving for that.

Cultural appropriation is something to approach with caution, care, and human empathy. But I think Anderson largely does exactly that.

And there's the other part of me that just wants to enjoy a movie that's pure charm, full of love, joy, creativity, excitement, sadness, and utopian hope. And at the end of the day, that's precisely how I feel about Isle of Dogs.

IMDB

Director: Wes Anderson

Producers: Wes Anderson, Scott Rudin, Steven Rales, Jeremy Dawson

Writers: Wes Anderson, story by Anderson, Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman, and Kunichi Nomura

Cast: Brian Cranston, Koyu Rankin, Edward Norton, Bill Murray, Jeff Goldblum, Bob Balaban, Kunichi Nomura, Ken Watanabe, Greta Gerwig, Yoko Ono

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for brief profanity and some violence, mostly cartoonish, but also mostly against dogs. Also, a weirdly graphic cartoon surgery sequence.

Budget:

Box Office:

Comments

Post a Comment